Catalogs of Deep Space Objects

Astronomers have always made lists, and over time these became known as “catalogs”. Recently, a project updating the NGC catalog discovered 82 others that list one or more NGC objects. Why so many?

The short answer is there are many aspects to astronomy, and the different lists help astronomers focus on what they care about.

Some catalogs try to be comprehensive. NGC listed every DSO then known when it was published in 1888.

In the modern era, of course, comprehensive catalogs are massive. The LEDA catalog started with 100,000 galaxies when first published in 1983, and now contains information on over 3 million celestial object, including more than 1.5 million galaxies.

Most modern catalogs are specialized, catering to narrow interests. Arp’s Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies, published in 1966, is among the most specialized. It’s one of my favories, however, but his interest happens to coincide with my own observing proclivities.

On this website, our database tracks our observations within the following catalogs, listed below in chronological order of publication:

- The Messier Catalog (M), by Charles Messier a French astronomer, initially published in 1774.

- The New General Catalog (NGC), by J.L.E. Dryer, first published in 1888. This was intended to be a comprehensive catalog of every known cluster or “nebula” (which then weren’t distinguished from galaxies) as of the date of publication.

- Index Catalog (IC), also by J.L.E. Dryer, first published in 1895 and updated in 1907. The IC was an extension to the NGC, expanding coverage to newly discovered objects. NGC objects are not found in the IC and vice versus, depending on the date of discovery.

- Sharpless Catalog (Sh2), by Stewart Sharpless, first published in 1953 with 142 objects (Sh1) and updated to 313 in 1959 (Sh2). The Sharpless objects are all H-III regions (mostly red emission nebulae), tend to be large, and often group separate NGC and IC objects.

- The Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies (Arp), a specialized catalog by Halton Arp, published in 1966 (Listings).

- The Caldwell Catalog (C), published in 1995, designates 109 of the most popular objects for for amateur astronomers that the Messier list missed.

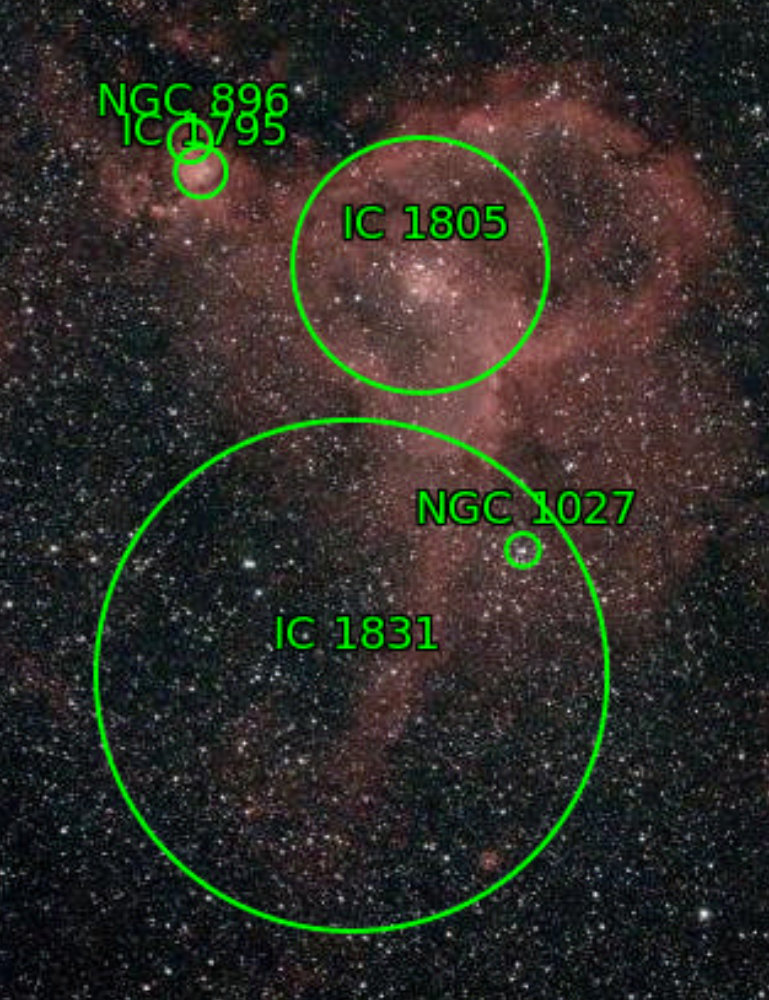

Why bother with so many? It turns out that the history of the catalog can give you some insight about the objects it contains, and just knowing the listing may help you observe it better. Check out the annotated image of the Heart Nebula above.

The Heart Nebula as a whole is designated by the Sharpless Catalog as Sh2-190. Note it contains 2 NGC objects, and 3 IC objects. The NGC objects are the brightest parts of the nebula, discovered prior to 1888. In fact, NGC 896 was discovered by William Herschel in November, 1787. NGC 1027 was also discovered by Herschel around the same time, but it refers to the open cluster of stars, not to the underlying nebula. All NGC objects were discovered visually. So, as an amateur astronomer doing EAA with a decent telescope and a CMOS camera, you should have no problem capturing it.

The IC objects were discovered some time between 1888 and 1908. There’s a good chance it was discovered by use of photographic plates rather than visually. These “objects” will be substantially dimmer than the NGC objects. In the case of Emission Nebulae, however, modern digital imaging techniques are very powerful, so an amateur with the correct filters can usually observe them pretty easily.

Galaxies are tougher. Unlike emission nebula, where modern filters really improve signal-to-noise ratios, observing galaxies require raw light-gathering power. By the turn of the 20th century, telescope optics were quite good. So, any northern hemisphere object which isn’t listed in the NGC or IC catalogs is likely to be quite dim… typically 14th magnitude or dimmer. Digital images and long exposures help the amateur, but a top pro astronomer with a high quality 20″ to 200″ telescope started with a major optical advantage.

Below we discuss the six catalogs we currently reference in this website.

The Messier Catalog – 1774

Charles Messier (1730-1817) was a French astronomer who specialized in “comet hunting”. He originated his catalog for a highly specialized purpose: as an aid to other comet hunters (a small but growing fraternity in the 1770’s) to identify nebulae that might be confused with a comet. This distinguished his work from “star catalogs” that mapped individual stars and which all astronomers used to locate targets. These have a long history starting with Hipparcus’ list of 850 stars published in 129 BCE. By the mid-18th century, then-current star catalogs mapped several hundred thousand individual stars.

Messier’s initial list, published in 1774, included 45 objects, 18 discovered by Messier himself. The list expanded in 1780 to 70, and the final edition published during his lifetime (1781) contained 103. Between 1921 and 1967, astronomer-historians expanded the list to its current, and presumably final, total of 110 objects, based on notes left by Messier or his assistant, Méchain, confirming they had observed them after the last publication date of their catalog in 1781.

In effect, due to the limitations of his telescopes, Messier’s list captured 110 of the largest and brightest deep space objects visible from Paris. When initially listed, all were described as “nebulae” (“nebuleuse” in French). This nebulous term (pun intended) described any fuzzy object visible in a telescope that wasn’t a comet: the key difference being that a comet, while orbiting around the sun, shifts position relative to other stars, whereas a nebula stays in a “fixed” position.

Today we sub-categorize Messier’s list into different types of objects, but descriptions evolved over the years. It started during Messier’s lifetime, when William Herschel, possibly the greatest astronomer of the 18th century and its most accomplished telescope builder, pointed out that many of the Messier “nebulae” were, in fact, star clusters. Herschel’s telescopes could resolve the individual stars whereas Messier’s inferior instruments could not.

It wasn’t until 1921 that Hubble published his paper proving that the Great Andromeda Nebula was, in fact, a distinct galaxy located far beyond the confines of the Milky Way. Indeed, the word galaxy derived from a Greek root meaning “milk” and originally referred specifically to the Milky Way. The term “galaxy” evolved into its current meaning during the 19th century when the debate grew heated over whether the Milky Way contained the entire universe, or represented only one of multiple galaxies. At the time, the astronomy “establishment” believed the Milky Way was everything. Hubble’s findings started a revolution which continues. Astronomers now believe that there are at least 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe, and one credible estimate places the number at 2 trillion.

Undoubtedly, the Messier list survives because it represents a “greatest hits” list of deep space objects. Whenever a new amateur astronomer first looks through binoculars or a telescope beyond the solar system, it’s most likely to observe something on the Messier list. Famous objects like “M1”, the Crab Nebula, “M13”, the Hercules Cluster, or “M33”, the Triangulum Galaxy, will be close to the top of anyone’s list, and the “M” appellations are short and easy to remember.

We provide a list of our observations arranged by Messier object here.

The New General Catalog (NGC) – 1888

Messier’s work was eclipsed by the Herschel family — William, his sister Caroline, and his son John — during the late 18th Century and into the 19th. Their Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars was first published in 1786 with approximately 1,000 entries, and expanded to 2,500 entries by 1802.

This expansion reflects both prolific observing by the Herschel siblings and their world-class telescope-building skills. In 1864, John Herschel published the General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (GC), with 5,079 entries, expanded posthumously to 10,300.

John Louis Emil Dreyer, a Danish astronomer working in Ireland, published a supplement to the GC in 1878. When he requested support from the Royal Astronomical Society in 1886 to produce a second supplement, they suggested he create a new edition of the GC instead. Published in 1888, The New General Catalog contained 7,840 entries, and was intended to capture every known DSO as of date of publication, correcting errors and duplicates in the GC along the way. Any DSO with a designation starting with NGC is listed in this catalog. It encompasses the great majority of objects that today’s amateur astronomers observe. As well, all of the Messier objects have a separate NGC listing.

Roughly speaking, the NGC represents the “state of the art” in astronomy at the end of the 19th century. A very high percentage of targets pursued by amateur astronomers are listed in the NGC catalog. We provide a list of our observations arranged by NGC catalog numbers here.

The Index Catalog (IC) – 1895

All NGC objects were detected and catalogued visually. Photographic plates started to be introduced a few years later, and precipitated an explosion of new discoveries, inducing Dryer to publish two extensions to the NGC, designated as the Index Catalog (IC) in 1895 and 1908 respectively. These represented a mix of visual and photographic finds. Such objects have catalog designation that start with IC. Compared to NGC, IC object are less often pursued by amateur astronomers simply because they are usually small and/or dim targets. Note that any given target will have either an NGC designation or an IC one (or neither in the case of objects catalogued after 1908), but never both.

We provide a list of our observations arranged by IC catalog numbers here.

Sharpless Catalog – 1959

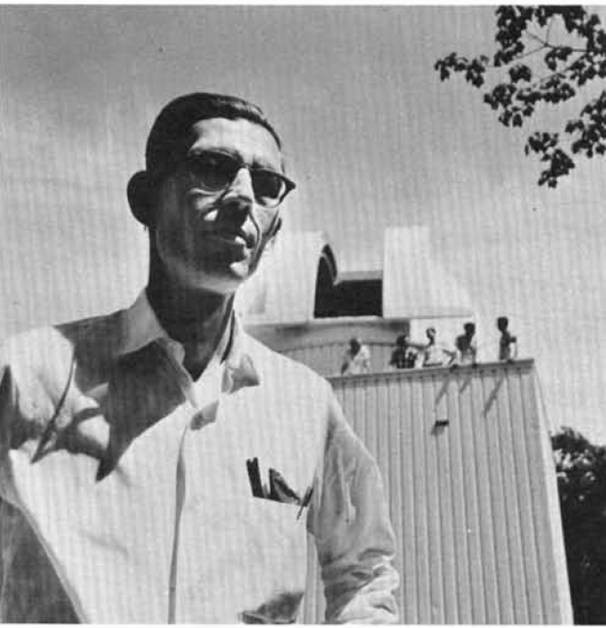

The Sharpless catalog is a list of 313 H II regions (emission nebulae) intended to be comprehensive north of declination −27°. Stewart Sharpless published the first edition, containing 142 objects, in 1953, and the second (Sh2), containing 313, in 1959.

Sharpless is a superb catalog for amateur astronomers, because many of the Sharpless “objects” are quite large and fun to observe with a small refractor and a digital camera. A pdf of the Sharpless Observing Guide is available here.

Personally, I really enjoy observing many of the Sharpless Objects, and his catalog is a much more reliable guide to these objects and their full extents than the NGC or IC listings.

Our listing of Sharpless objects we’ve observed can be found here.

Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies – 1966

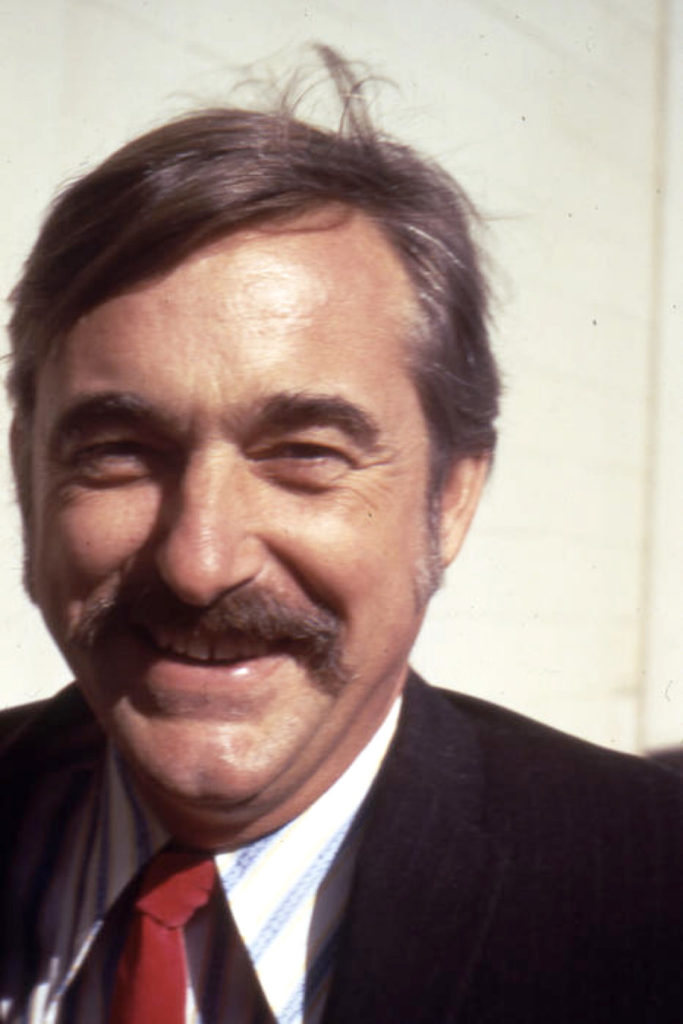

Halton “Chip” Arp, author of this atlas, was quite a character. Earning his Ph.D. from Cal Tech in 1953, his first job was assisting Edwin Hubble in finding supernovae within the Andromeda Galaxy using the 200″ Hale telescope on Mt. Palomar in California. At the time, and for many years, this was the leading telescope in the world.

Arp spent 29 years at Palomar. For much of the time, he was a senior observer there, creating many of the images published in the Hubble Atlas of Galaxies which invented and described in detail the galaxy classification system now in general use.

But Chip was a contrarian, and was aware of galaxies that didn’t fit readily into the standard classifications. In a word, “Peculiar”. His Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies was published in 1966. While out of print, the Atlas is available online here.

My particular interest in Arp’s designations are two-fold. First I love peculiar galaxies, and did so, even before I knew they were a “thing”. Second, I’m participating in an Astronomical League program to observe at least 100 of the 338 northern hemisphere listings.

We provide a list of our observations arranged by Arp Listing here.

Caldwell Catalogue – 1995

This is the only list we track which was intended from inception to be used by amateurs. Developed by a well-known British amateur astronomer and educator, Patrick Caldwell-Moore, and published in 1995, it was consciously designed to include the next most popular targets after the Messier Catalog. So Moore listed 109 objects, the same as the Messier catalog at the time. Because Messier objects were already designated as “M”, Moore referenced his middle name and used the prefix, “C”.

All but a handful of Caldwell Objects are listed in the NGC, 7 are IC objects, one is Sharpless, and one is from the Melotte Catalog of 245 star clusters published in 1915. Our Caldwell listings can be found here.