Messier Objects

Page 4 of 11

Messier observations 31-40 of 110 total to date.

| Catalog # | Thumbnail | Title/link | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

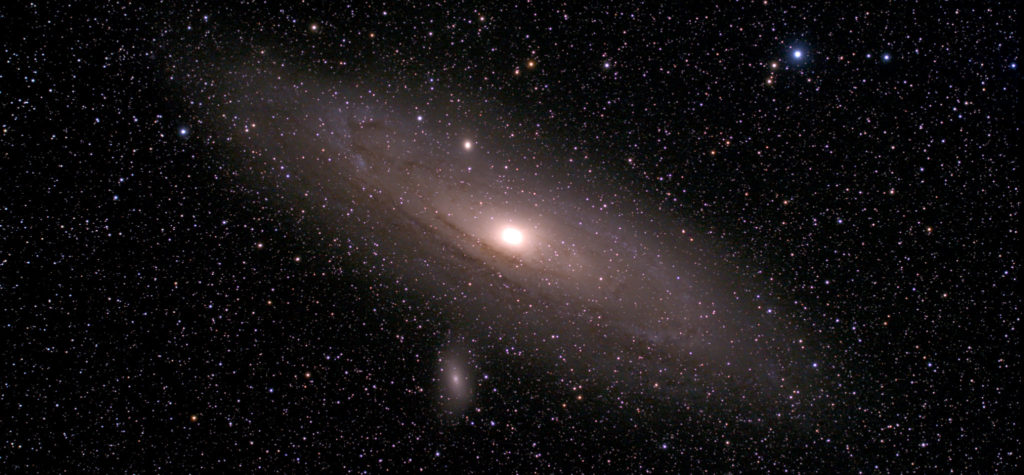

| M31 |  |

M31 / Great Andromeda Galaxy | Messier recorded this target on August 3, 1764 attributing discovery to Simon Marius, who'd described a telescopic observation in 1612. Neither was aware that the Persian astronomer Abd-al-Rahman Al-Sufi, had recorded the "little cloud" in his Book of Fixed Stars in 964 AD [messier.seds.org]. <--> This is a stunning spiral galaxy with two close companions: M110 in the foreground, and M32 just peeking over the disk. The brightest section is the galactic center and is presumably the only section Messier could see -- he measured the diameter at 40' whereas modern measurement puts the size at 178' x 70'. This is a target I've observed dozens of times: when it's visible, it's by far the most popular star party EAA target. It rewards all levels of integration from 60s to hundreds of hours. This is one of my favorites, captured on a beautiful clear November night. The 30m integration in this view, provides a decent perspective on the full extent of the galaxy, and enables the dust lanes to be clearly visible. I have attempted longer captures, but this remains my favorite due to the clarity of the night. |

| M32 |  |

Arp 168 / M32 | Messier recorded this object on August 3, 1764, the same date as M31, and attributed discovery to Guillaume-Joseph-Hyacinthe-Jean-Baptiste Le Gentil de la Galazière in 1749. <--> Note: this is the first of 11 Messier Galaxies that Halton Arp selected for his Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies. I developed this description as part of my qualifying for the AL Arp Observing award. This is a very famous galaxy, mostly imaged with its dominant partner, M31. It is extremely bright. I had fun with this, as I've never understood why Arp labelled it "peculiar", and after this "deep dive", I'm still skeptical. The recorded remarks on Arp 168 read as follows: "Faint diffuse plume curved away from M 31 disk." To be clear, M32 looks like a dwarf elliptical galaxy, which might qualify as peculiar by itself. But Arp's category here is defined by "diffuse counter-tails". As I understand it a counter-tail is an asymmetrical dust plume, today understood to be the result of a merger or impending merger. So, to test the "remarks" clarification, I needed to figure out what direction is Andromeda. So I converted my observation to an inverted image, and overlaid it on a personal capture of Andromeda (image 2). I then drew a line from the Center of M32 to M31 on top of my overlay, and cropped out the relevant bits (image 3). Note I left the overlay semi-transparent so you can judge the accuracy of the overlay. Then I took that overlay and placed it back on my original M32 inverted capture... placing an arrow on top of the line indicating towards M31's center (Image 4). -- At this point I removed the overlay to see my inverted capture, knowing the direction to Andromeda (Image 5). Do I think there is a longer plume due south, away from Andromeda? No. Arguably there is an extended plume SW (to lower left corner), but does that count? And is it enough to qualify M32 as peculiar? Just in case there is something about Arp's own capture, I overlaid it on this (image 6). Does it confirm a due south asymmetry? Not to my eye, and the posible SW asymmetry is not confirmed either. So, I continue to be skeptical of this one. |

| M33 |  |

M33 / Triangulum Galaxy / NGC 598 | Messier recorded independent discovery of M33 three weeks after M31/32 on August 25, 1764. Later scholarship established it had been observed by Giovanni Battista Hodierna, an Italian astronomer, prior to 1654. Presumably the delay is attributed to the time it took to "discover" Triangulum, and then one or two more observations to confirm the nebula was staying fixed. <--> Triangulum is the second-closest major galaxy to the Milky Way after M31. Its apparent magnitude of 5.7 (compared to 3.4 for M31), makes it 8x dimmer and a much more challenging naked eye target. Triangulum was one of the first galaxies I attempted when I started EAA. I've been intrigued by its grand spiral design and that it would fit within the FOV of my first telescope -- an SCT with reducer (which M31 would not). You'll find a couple of other observations in the gallery including 1) a wide-field observation using my Askar V at 600mm in December of 2023 and 2) a heavily processed view taken in late 2022 using my original C9.25 which clearly shows a series of pink-fringed star-forming regions such as NGC 604. |

| M34 |  |

M34 / Spiral Cluster | M34 was probably first found by Giovanni Batista Hodierna before 1654, and independently rediscovered by Charles Messie on August 25, 1764. <--> This is an attractive open cluster characterized by a couple of dozen giant blue stars, and a smaller number of red ones, many of which appear to be doubled. Whether these are physical or optical doubles is unclear; I suspect some of both, |

| M35 |  |

M35 / NGC 2168 | Messier cataloged this object on August 30, 1764, attributing discovery to John Bevis, although that honor is usually assigned to Philippe Loys de Chéseaux who observed and cataloged it in 1745 or 1746. This is a tight cluster dominated by blue stars, with a few red giants thrown in. <--> For me, this was the second capture of a strange evening when it rained right up to the moment it cleared around 9 PM. Because of the 93% moon, I had planned to capture a number of Messier objects, mostly clusters, using my EdgeHD. However, because of the late rain, I couldn't set up in advance, so I decided to observe with the SeeStar instead. M35 is a very bright cluster. NGC2158 just below (southwest) of M35 gives it an exotic look. It appears to be a small, globular cluster, but according to Wikpedia, it's actually an old, metal-poor open cluster. |

| M36 |  |

M36 / NGC 1960 / Pinwheel Cluster | Modern scholarship attributes discovery of this small open cluster to Giovanni Batista Hodierna before 1654. It, along with M38, was independently discovered by Le Gentil in 1749. Charles Messier was probably aware of this, though his catalog entry for September 2, 1764 is silent on discovery. <--> The Pinwheel Cluster moniker is presumably motivated by the rough pentagram shape of the blue giant stars which includes at least three doubles. This was my third capture of a strange evening when it rained right up to the moment it cleared around 9 PM. Because of the 93% moon, I had planned to capture a number of Messier objects, mostly clusters, using my EdgeHD. However, because of the late rain, I couldn't set up in advance, so I decided to observe with the Seestar instead. |

| M37 |  |

M37 / Salt and Pepper Cluster | Messier recorded this open cluster on the same day as M36, September 2, 1764. Le Gentil had missed this cluster when he rediscovered M36 and M38 in 1749, and Messier was probably unaware that Giovanni Batista Hodierna had recorded it before 1654. So it's likely Messier believed he'd discovered it himself. His entry describes, "Cluster of small stars, little remote from the preceding [M36]....The stars are smaller, more close together". <--> The salt and pepper moniker presumably refers to the mix of blue and red stars and the seemingly random pattern of stars, like salt and pepper spilled onto a table. |

| M38 |  |

M38 / NGC 1912 / Starfish Cluster | Like M36, modern scholarship attributes discovery of this small open cluster to Giovanni Batista Hodierna before 1654. It, along with M36, was independently discovered by Le Gentil in 1749. Charles Messier was probably aware of this, though his catalog entry for September 25, 1764 (3 weeks after M36/37), is silent on discovery. <--> This cluster features an inner and outer pentagram etched by predominantly blue stars, though Messier's entry describes it as "square". This was the fourth capture of a strange evening when it rained right up to the moment it cleared around 9 PM. Because of the 93% moon, I had planned to capture a number of Messier objects, mostly clusters, using my EdgeHD. However, because of the late rain, I couldn't set up in advance, so I decided to observe with the Seestar instead. |

| M39 |  |

M39 / NGC 7092 Revisit | Messier is credited with discovering this open cluster, recorded on October 24, 1764, nearly a month after M38 (his 17th so far). He notes: `Cluster of stars near the tail of the Swan; one can see them with an ordinary telescope of 3.5 feet [FL].' <--> As a "cluster" this is one of the least dense in the Messier Catalog. Nebulosity around several of the larger stars provides some interest. |

| M40 |  |

M40 / WNC 4 | This is the only double star in the Messier catalog, now credited to Messier (#18) and recorded on October 24, 1764. Messier's own motivation was to confirm the observations of Johann Hevelius, the influential 17th century astronomer from Danzig (Gdańsk), in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Hevelius had invented many celestial cartographic conventions, and no doubt heavily influenced Messier's own comet map-making. As Messier wrote, "I searched for the nebula above the tail of the Great Bear.... I have found, by means of this position, two stars very near to each other & of equal brightness, about the 9th magnitude, placed at the beginning of the tail of Ursa Major.... There is reason to presume that Hevelius mistook these two stars for a nebula." <--> This was my fifth capture of a strange evening when it rained right up to the moment it cleared around 9 PM. Because of the 93% moon, I had planned to capture a number of Messier objects, mostly clusters, and decided to observe with the Seestar. This is an "optical" double, two stars that just happen to appear close together from Earth's vantage point. |